This is part one of a two part series on the Army / Navy football classic as told by West Point graduate Jeff O’Neal of Paris. This year’s game will be played on December 11. The second part of this series will publish on Saturday, December 18.

It’s Thanksgiving Day, and while most of us are spending the day with family, eating, and watching our favorite Thanksgiving Day football game, there are members of the U.S. military who are stationed both at home and overseas watching over us and protecting us all. So, for starters, I want to thank all of the members of the military, both past and present, who protect us all so that we can enjoy days such as today. Our debt to you is enormous, and we can never fully repay what each of you has done for all of us.

But there is no doubt that football is a part of the Thanksgiving Day tradition for many, and today will be no different. And perhaps the most meaningful game of them all is not actually played on Thanksgiving Day, but played in early December: the annual Army / Navy football game. Historically, the game was played the first weekend in December. But when Power Five conferences began playing conference championship games on that weekend, the game was pushed back a week for a national television audience. So on that weekend in December, the only college football game played that day and that can be watched on television is the Army / Navy Classic.

The traditional battle between the two most prestigious military academies is packed with tradition and meaning. There are traditions and customs that are highlighted by the television networks during their broadcasts each year, and there are those that only former cadets and midshipmen close to the programs know and remember. But to me, your writer, the most significant impact this game has on me is knowing that each player on the field, and each cadet and midshipman in the stadium, will serve our nation, including service in all parts of the world, and in some cases, in all conflicts and theaters of war. On game day, they give it their all, and on “game day” in service or in battle, they give it their all.

As part of my coverage of Paris sports, I make many acquaintances. People who have played for the Eagles, parents, student-athletes, and community members. One such acquaintance I have made is that of retired Army colonel Jeff O’Neal of Paris. Colonel O’Neal is a West Point graduate and served a distinguished career in the United States Army as an officer at many levels of leadership and appointments throughout the world. Recently, I had the pleasure of sitting down with Jeff to interview him about his career, his experience at West Point, and the meaning of the annual Army / Navy game. I recorded over two hours of his experiences that he shared with me, and I have to tell our readers…I found every minute of his interview to be fascinating. In fact, I could listen to Colonel O’Neal for hours!

But before we get into his interview, it is noteworthy to provide a little background on the Army / Navy game itself. In fact, it is much more than a football game to many. But from a football perspective, it represents all that is pure in the game of college football. Few, if any, of the players on either side will ever have a chance to play professional football upon graduation. And if you extend this to the United States Air Force Academy that was, originally, designed and organized from the “blueprint” of West Point, with the flight restrictions on an airman’s size and weight, the chance of an Air Force graduate playing professional football are even more remote.

To the players at Army and Navy, they are focused on playing on our nation’s team, the U.S. military. And the game is a national treasure, a tradition where football fans and citizens alike stop to watch the only game that is played that day. It is always nationally televised, and it is a fan favorite. Every player gives it their all, and every player plays with heart and emotion. The players may not be as big, their team speed may be a bit slower, and they may not be playing for a national championship, but, football fans would not trade this game for anything.

The United States Naval Academy traditionally plays the University of Notre Dame, as well. Why is that noteworthy? Because during World War II, Notre Dame was having financial problems and was having difficulty sustaining operations as a university. The Naval Academy struck an agreement with Notre Dame to use part of its campus as a training facility, and the revenue paid to Notre Dame by Navy was enough to keep the university in operation. Since that time, Notre Dame vowed to always invite Navy to play every year in football. No doubt, the annual game produces revenue for both schools, and the promise to play was a way of repaying the Naval Academy for coming to its rescue financially during a very tough period in its history.

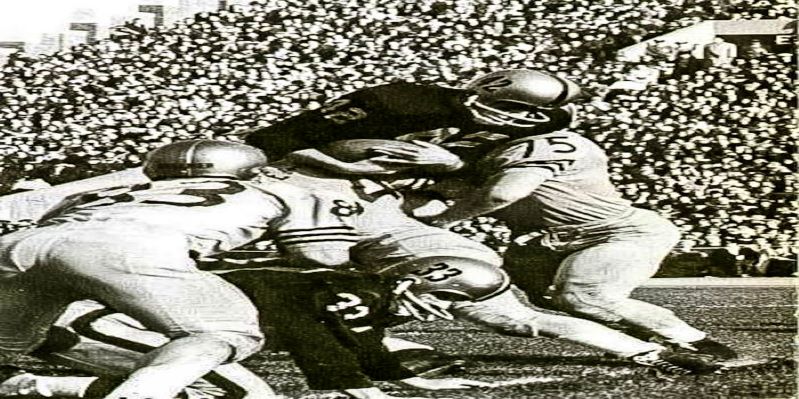

In 1963, Navy defeated Army 21-15. Navy’s All-American quarterback, Roger Staubach, led the number two-ranked Midshipmen to victory with the Army comeback falling short at the Navy two yard line. But with all of its dramatics, that was not the story of the day. The game took place on December 7, 1963, approximately two weeks after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Roger Staubach had just won the Heisman Trophy a few days before President Kennedy’s assassination, and the question became should the game be played as scheduled. Some say that the Kennedy family wanted the game to be played in honor of the President who had served in the Navy himself. But regardless of who influenced the decision to play, the game was played before 100,000 people at Municipal Stadium in Philadelphia, and the game itself gave millions of Americans a brief reprieve from the mourning of their President’s death. Players on both sides played their hearts out, just as they always do, and the result was a dramatic finish that saw Navy go on to the Cotton Bowl to play Texas.

Fast forward to 2001 when the Army / Navy game followed another national tragedy; the attack on 9/11, and was played on December first of that year. Again, playing in Philadelphia, which is traditionally played there because it is geographically the approximate halfway point between the two military campuses, both teams did not enter the game with good records. But significantly, the game again helped the nation move forward. Tragically, and serving as a reminder of the true significance of the game, two players in the game were later killed in action as they served their nation. Army cadet and later officer J. P Blecksmith was killed by a sniper in Iraq in 2004, just three years after the game, and in 2010, Navy lieutenant Brendon Looney was killed in a helicopter crash in Afganistan.

So, when I went to Colonel O’Neal’s office in Paris for his interview, I was excited with anticipation as to the stories he would tell. But I must confess that my head was swimming; there was so much I wanted to know, but in fairness to our readers, I struggled with how to succinctly tell his story where it would make sense to you all. But very soon after I met him at this office, I was greeted with him fully adorned, wearing an Army football jersey, and was shown photos of his son who is a junior at West Point, and another son who is a graduate of Missouri University of Science and Technology. And oh by the way, they have a daughter, Rachel, who is a junior and played on the state championship Paris High School volleyball team this year!

Colonel O’Neal is rightfully proud of his service and his experience at West Point. In fact, if you look up the admission data on applicants to West Point, the admission rate is 10.3%. So, for every 100 applications to attend college at the United States Military Academy, approximately ten are admitted. And those ten are admitted conditionally pending “nomination”, meaning they must be nominated by a United States Congressman. In Colonel O’Neal’s case, he was nominated by former congressman John Paul Hammerschmidt. Hammerschmidt represented the third congressional district in Arkansas from 1967-1993.

Jeff works as a financial planner for Edward Jones of Paris. Not surprisingly, Jeff has been a success in every work of endeavor he has ever attempted throughout his adult life. But it is a long way from his days as a student and later graduate at County Line High School, studying at West Point, serving a long and successful military career as an officer, and upon retirement from the military, working as part of the high school faculty at Subiacco Academy before entering into private business. Jeff has a wonderful and very interesting story, and it is our pleasure at Resident Press to bring it to you.

Jeff graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point on May 31, 1990. When I asked about the start of Jeff’s subsequent military career, he began by saying, “I was commissioned as a field artillery officer, and went on to serve over 25 years; 25 years and five months. I got to go to several places.” I invited Jeff to tell me about those places and he then told a story that fascinated me for over two hours.

He began his story by saying, “To start off, I went to Fort Sill, Oklahoma to field artillery school. You do your basic training there; officer basic training course. Then I went to the First Cavalry Division; working with multiple-rocket launching systems. The rockets, as a platoon leader, so as a 22 year-old, I had the responsibility of a $9 million system and 25 soldiers under me. So, it was pretty cool. I became the second in command of that battery. I did that for about two years, and then became an executive officer of a cannon battery. I really enjoyed that because you are out in the field more, shooting, and I was in charge of all of the maintenance and logistics of the battery. From there, I went back to Fort Sill for the officer advanced course and then on to the Republic of Korea to a place called Camp Hovey which is about 15 miles from the DMZ (demilitarized zone). So in Korea, there was a certain seriousness added to my experience to that point. That was in 1994-95. When the regime in North Korea was ramping-up, we had two pilots in a helicopter crash across the DMZ. Tensions were pretty high. We worked approximately 90-100 days straight without a day off. We trained artillery to go to certain battle positions in case anything ever started. Then, I started off as a battalion plans officer; which meant I put together the war plans, rehearsals, training, and exercises. Then I became the adjutant or human resources person. We processed all the issues that soldiers really care about such as pay, awards, evaluations, travel and leave.”

After Korea, Colonel O’Neal went to the 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. “I spent almost four years there. I was a captain there. During that same time, I went to Ranger school there, as well and went to the Ranger program in the winter. As an officer at Fort Campbell, I was the person who coordinated the artillery fire, mortar fire, and close air support fire. That was a great job. I had a great group of fire supporters, observers, that work with the infantry battalion. So, I did that for about a year and a half, and then became a battery commander. I was in command of a 105 firing battery. Loved this job; was probably my favorite job in the Army because it was fast-paced. You’ve just got to know what your doing. It is the Army way; you get to demonstrate your competence every day. It doesn’t matter who you are or where your from; you get to demonstrate your competence every day.”

Colonel O’Neal’s job performance with the 101st was exemplary, and as a result, he was nominated and placed as an observer / controller at the Joint Readiness Training Center that meant that “you coach, mentor and make sure people are safe in the training rotations. So, I got to see every rotation go through there, and I got to work with some phenomenal guys. So, for two years, I did that. My son Jackson was born there, and my other son Beau, who is now at West Point, was born after that. “

From Fort Polk, Louisiana, Colonel O’Neal was selected again to a very prestigious position at Command and General Staff College. “And, 09/11 happened. I’m a major now, and at the College, it was kind of like a draft pool. All of these units wanted to get you to their units. So, you interview with people. I wanted to be in the action, and at that time immediately after 9/11, we were graduating in May 2002. So, I started to look at going to the 10th Mountain Division. I knew one of the battalion commanders there from Korea. He wanted me to go to Fort Drum so me and one of my buddies decided that we were going to be two majors who go to Fort Drum (New York) from the field artillery. Fort Drum is near the Canadian border, and it is very cold and very snowy, so credit to my wife Michelle for agreeing to go there. Everyone was gearing up for war in Afghanistan. I was coordinating fire for brigades of approximately 5000 troops. Things started creeping up in Iraq and rumors were out there that we would be part of the invasion in Iraq.”

And then, as it often does, Colonel O’Neal received orders to “pack his bags”, he was going to Italy. “I went to go see the battalion commander and he said to pack my bags, I had like two days, I was going to Vicenza, Italy, to work with the 173rd Airborne Brigade. Orders were for the 10th Mountain to be attached to the 173rd and then go into Iraq to open up the door to the front. So, I don’t even know if we are going to war or not, but I am packing my stuff and I eventually walked right into rehearsals for airborne support for Iraq. When “Shock and Awe” had started on March 17, my guys stepped off one flight line and walked to another to go to the war in Iraq.” Colonel O’Neal’s force seized the town of Kirkuk in Iraq the same night that Baghdad fell.

During the occupation of Iraq, Colonel O’Neal’s 10th Mountain Division that was attached to the 173rd Airborne, set up counter fire artillery. After the regime change in Iraq, O’Neal’s commander return to the states and Jeff became in charge of the unit in Iraq. “We set-up the government of Kurkuk which was a province of approximately 850.000 people at the time. So, we did things initially like set up banks, set up detention centers, and working with the guys who were just elected to the government. So, you had Kurdish, Turks, and Arabs elected to the city council. So, me and my staff, which was a major, two captains, and three lieutenants and like a couple of sergeant first class, we started working with the city council. I met with city council chairman every day. I met with the governor of Kurkuk every day. It was kind of like, this is what we need to do today. That’s when we realized that things culturally are different in America. But, you adjust and overcome.”

As Colonel O’Neal’s story continued, I became more and more amazed at the variety of experiences and responsibilities that he had in his career. At one point in his interview, I asked him if had felt prepared to do things like train personnel, set-up governments, etc. He responded by saying, “It was a challenge, and it was on the job learning. But a lot of it was just growing up in the Army, being at West Point, and always having been put in situations where you have to figure things out. Ranger School was a lot like this too, so you just have to persevere and know that you are going to find a way. A lot of trial and error, but you learn from your mistakes. Looking back, we were not specifically trained for those things, but through the training and education that you get in the Army, you just use your ingenuity and find a way.”

Colonel O’Neal served as an officer with now Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Mark Miley. Miley served as O’Neal’s brigade commander in 2004. O’Neal’s unit spent the better part of the spring that year preparing to go back to Iraq. In fact, he remarked, “I am sure to Michelle, it seemed like we were already deployed.” In June, the unit first went to Kuwait and later to Baghdad. I was second in command and often served as the acting battalion commander, speaking with now General Miley, everyday.

The year of 2005 was eventful for O’Neal in both good and bad ways, and he admits that the year is one that sticks in his mind. “On January 1st we lost our first soldier, and a week later we lost another soldier. So, 2005 is an “interesting” year for me for various reasons. The first soldier that died on January 1 as a second generation Hatian immigrant from New York City who had volunteered for a patrol that day and lost his life from an IED (improvised explosive device.) The soldier who died a week later was from Minnesota from a Native American Indian reservation and he too died from an IED.

I asked Colonel O’Neal about how this affected him as both a person and as an officer who lost men under his command, or he himself and his exposure to dangerous situations that could lead to additional loss of life. Jeff responded by saying, “We knew going in that it was not a matter of “if” but “when” with respect to taking casualties because of where we are. It’s just a way of life, and you just have to know that it could happen every day. I went on patrol and into a lot of bad places a lot. I am still in contact with those guys. They came through and did a great job. Michelle will probably tell you that I have not slept very well since 2005. At West Point they put you under stress, and it is about being able to accept failure sometimes and learn how to react and learn from it. So, you have to react under stress.”

Jeff will tell you that his wife, Michelle, was very important in her role in both their marriage and her support of Jeff’s service in the military. Jeff commented that in 2005, “On the home front, Michelle was raising two boys and later was pregnant with Rachel. So, she is going through that and raising two boys, and was due in January. Rachel was due on January 19th, and I had already talked to my commander about going home at that time. I told Michelle that I could not be home on January 19th and that she would have to put it off (Rachel’s birth) for a couple of days. So, I made it home on the night of the 20th and then Rachel was born the next day.”

Colonel O’Neal served in Hawaii in one of his final leadership positions performing such functions as being responsible for logistics and operations in the Pacific with duties that included briefing not only his superiors but members of Congress on budgets and requested funding for operations in the Pacific. But Hawaii would not be O’Neal’s final theater of service; as he eventually closed out his career with a third tour of duty in Iraq. Indeed, West Point provided the foundation for his career, and Jeff served all over the world and at various levels of command with distinction as an officer and as a West Point graduate.

So, when one looks at the military career of Jeff O’Neal, you can close your eyes and imagine the careers, experiences, and levels of command that the cadets and midshipmen both on and off the field at this year’s game will experience after December 11. Jeff shared with me the experience of this awesome game and its traditions.

“The very first day (as a cadet) it is about “Beat Navy.” Among all of the craziness going on in your life at that time, it is the one thing that unifies everyone; upperclassmen and plebes. So, huge deal, and it was always kind of a relief to the plebes that you could go the “Beat Navy” route. A lot of times, you could fall back on Beat Navy. If you say Beat Navy, maybe some kind of grace would be given to you. Even on exams during game week, if you put a Beat Navy on your paper, you might get a bonus point or two.”

“So plebe year, you are part of the fourth class system. Which meant that you got hazed and duties you had to do. And you always did it under pressure. Anytime you went to an upperclassman’s room you are subject to harassment.”

A tradition of the game, the “Prisoner Swap” includes a portion where Midshipmen attached to West Point, and Cadets attached to the Naval academy would be sent back to their home sides for the game.

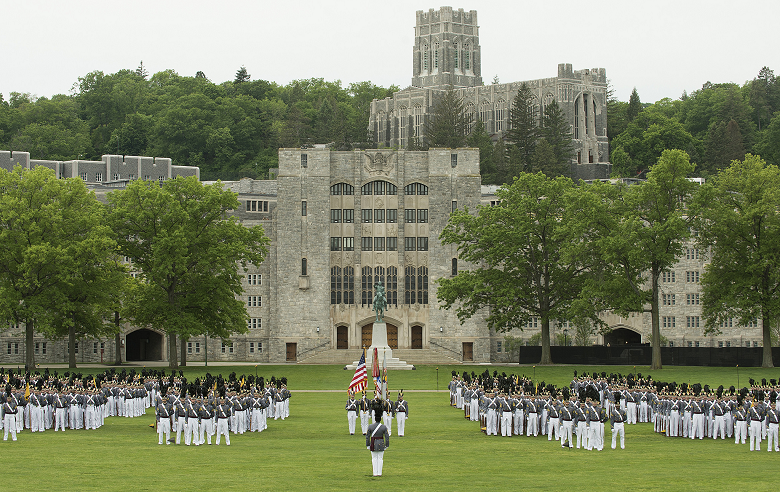

But perhaps the most visual and well-known tradition is the march of the Cadets and Midshipmen onto the field prior to the game. On December 11 of this year, Colonel O’Neal will be at the stadium to watch his son Beau participate in the march just as he did in the late 1980s. One week after the game, Resident Press will pick-up Jeff’s story from here.

Part two of this story will publish in Resident Press on December 18. Following this year’s game on December 11, watch for Colonel O’Neal’s story of his visit to the game to watch the annual rivalry and to see his son march onto the field during the pregame ceremony. Colonel O’Neal has graciously agreed to share his photos from the trip, and we will publish them for our readers in Resident Press.

So until then, on behalf of all of us from Resident Press, we wish you and your family a Happy Thanksgiving, and we hope you enjoy the day with your families and others whom you love and who love you. We all have so much to be thankful for, and on this day, we thank everyone in the military, especially those who cannot be home today. Thank you all from the bottoms of our hearts for your service to this great nation.

Happy Thanksgiving, and watch for the conclusion to this story on December 18 in Resident Press.