By Dr. Curtis Varnell

Growing up, virtually every rural farm had at least one jersey milk cow. The jersey resembles a large deer, both in color and size, with large soft eyes and a gentle demeanor that make them ideal for the milk herd. Milking the cow was a daily morning and evening routine, providing the milk, butter, and dairy products for the family.

Both sides of my family were at least part-time farmers, and both made extra income by selling excess eggs and butter in local markets. Jersey cows produce milk with a lot of butter fat which would be separated from the milk, churned, and then placed into molds which produced a pound of real butter. The milk left in the churn was clabbered and, with a little added salt, was consumed as butter milk.

Traditionally, this method of producing and consuming milk products goes back into antiquity. The first milk cows arrived in Arkansas along with the first permanent settlers. Animal herds and urban life do not mix well. As towns developed, farmers in the surrounding areas began producing excess dairy products and delivering it for sale to their urban neighbors. Shortly after the Civil War, Eleithet Coleman became one of the first to deliver fresh milk to homes in Pulaski County. He and his son Fred milked some fifty cows daily, placing the milk into large dairy cans, and delivering it to homes. It was sold in quarts, ladling it by dipper out of the large cans into the buyers containers. In 1915, Walter and Gladys Coleman introduced the use of bottled milk and the trend expanded throughout the state. Most school children of the 50’s,60’s, and 70’s remember the glass pint jars of chocolate and white milk consumed as part of school lunches.

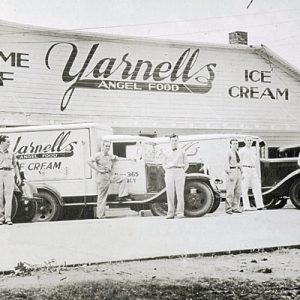

In the 1940’s, Coleman Dairy installed the modern pasteurization process, and this allowed for longer and safer storage of milk products. In 1932, one of my favorites, Ray Yarnell, started the production of ice cream at their factory in Searcy.

Arkansas, especially the northwest corner of the state with it rolling hills and ample water, was an ideal location for dairy farming and a thriving industry developed. Aided by the U/A cooperative extension service, farms increased production through the use of mechanical milkers, using the larger Holstein cow, and better feeding practices. By the 1960’s, large cooled semi-trucks were making daily visits to area dairy farms, picking up thousands of gallons of milk, and delivering the milk to urban factories to be processed. At that time, dozens of farms dotted the countryside from the Arkansas River valley north to the Missouri border. The George Huber farm near Subiaco was recognized as one of the top five herds in the U.S. and dairy farming was a major part of the regional economy.

Just as quickly, the milk industry faded. By the mid-1980’s, federal deregulation of milk prices and competition from huge “milk” factories, contributed to such a decline in profit that farmers began to shift to other products or just simply selling out and moving into cities. In 1989, there were 852 producers in the state, by 2009 there was only 140, and today even less. Coleman Milk sold to Highland and eventually to Prairie Farms. Yarnell’s ice cream closed their plant in 2011.

Virtually all the milk products used in Arkansas today come from out of state. The dairy products you use are produced at “milk” farms with an average size of 337 cattle per herd. In 2017, 189 of those farms had more than 5,000 cattle. The average dairy herd in New Mexico has over 2,500 animals on one farm!! Those cattle are not the small gentle Jersey but a hybrid Holstein that can produce 13,000 pounds of milk per year. Peak production has moved to large farms where cattle are housed, not on the rolling green hills of Arkansas, but, more often in small feed lots in California, Texas, and New Mexico.

I miss those early morning visits with my grandparents, listening to the two Jersey cows bellowing in reply to grandma’s insistent calling. Sitting on her stool, she would quickly strip the cow of its milk, leaving one teat for the calf she released as she finished milking. Afterward, she would strain the milk and cool it for our use.

Reverting to the old days, some area farmers are now producing and selling raw milk. My sister recently purchased some near Dardanelle and there seems to be a developing market for the “natural” Arkansas produced product. The taste? If you tasted those cardboard, perfect-shaped tomatoes and then compared it to those heritage tomatoes produced in the Arkansas sunshine, you know there is no comparison. The same can be said for the “natural” milk but after years of pasteurized, homogenized, etc. milk, one would have to say that real milk is an acquired taste.