By Dr. Curtis Varnell

Little remains of the two Arkansas internment camps that housed Japanese during World War II. Located in the flat rural delta areas of the state, few individuals even realize that the camps ever existed. A dark blight on our history, thousands of Japanese living on the west coast were rounded up by the U.S. government and placed in internment camps in ten isolated areas scattered across the country. The “internment” centers, little more than prisons in Arkansas, had barbed wire fences and armed guards with totally controlled entrance and exits.

The story began years before the onslaught of the war. Thousands of Chinese had immigrated to the U.S during the California gold rush. Competing with white Americans for mining claims and later for prime farming locations, created racial animosity and prejudice. By 1870, Chinese comprised about ten percent of the population of California. The U.S. government passed a series of Chinese exclusion acts to prevent immigration from China. With Japan opening for trade, Japanese immigrants began to fill the labor niche. Soon, the discrimination and prejudice shifted to the Japanese and California passed a series of laws excluding the Japanese from immigrating, buying agricultural land, or even leasing property or sharecropping. Some of these feelings and resentments created the animosity that eventually resulted in WWII.

After Pearl Harbor and America entering the war against Japan, many people living on the west coast feared an imminent attack from Japan and felt that the local Japanese population would provide needed assistance to their mother country. It should be noted that over two-thirds of this feared population were full American citizens and had live in the states for over two generations. It should be noted also that individuals of German or Italian ancestry were never rounded up for internment camps.

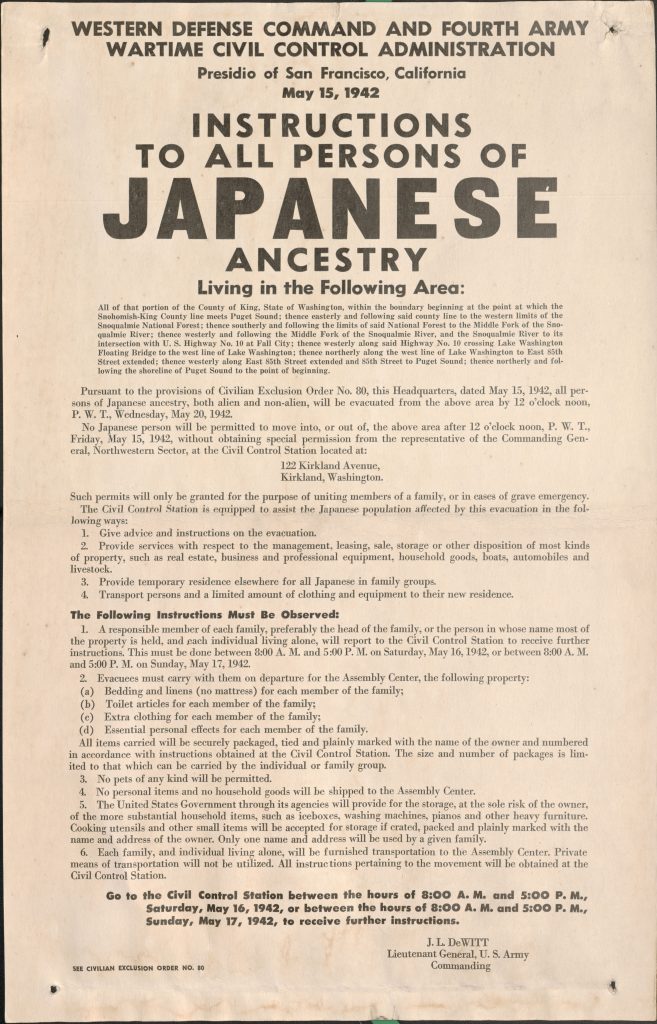

Over eighty percent of all Japanese Americans lived in Washington, Oregon, and California. Fueled by fear and war hysteria, the population of these states demanded action and President Roosevelt responded by executive order 9066 which empowered the secretary of war to designate exclusion areas where Japanese could not visit. A later act set up camps within the isolated interior of the U.S. which would house the Japanese-Americans until the end of the war. The Japanese-Americans were given days to get their property in order and report to relocation sites.

Two of the ten sites were in Arkansas, both in isolated regions of the delta. The government had thousands of acres of land that had been confiscated during the depression because owners could not pay taxes. Both Arkansas sites were in the marshy, wet, and humid areas of Desha and Chicot counties and were located adjacent to rail systems that could easily deliver the Japanese-Americans to their new homes. Each camp was composed of about 10,000 acres. The government, at an expense of about ten-million dollars, build complexes of tarpapered, A-framed buildings in large numbered blocks. Each building was 20 by 120 ft. long and divided into four to six family units. Laid out in typical military precision, each block consisted of fourteen residential buildings and would service about 250 people. Each block had a laundry, recreation hall, and communal latrine. The camps were surrounded by wire, had guard towers, and rules were enforced by the military police.

A black mark on the history of Arkansas, Governor Homer Adkins did everything possible to take away the basic human rights of these people, a fourth of whom were children. He refused to allow the students to attend college, fearing it would eventually result in integration. He, along with the legislature, passed the Alien Land Act to prohibit any Japanese citizen form owning land in the state. He also refused to allow any of the Japanese to leave camp or to get outside work, even though their labor was needed during the war years. Other camps in other states allowed much more freedom and encouraged the Japanese-Americans to work.

Of the 16,000 or so Japanese located in the state, few chose to remain at the conclusion of the war. Some of those from the camps went on to fame; probably the best known in Arkansas being George Takei (Star Trek’s Mr. Sulu). It should be noted also that many young Japanese men volunteered and fought for the U.S. during the war. After the war was over, many returned to California to find their homes confiscated from failure to pay taxes, others found their property destroyed and, and most still found animosity from neighbors because of their national origin. Though little remains of either the Rohwer or Jerome camp, one can visit the sites. Arkansas State University has provided interpretive sites and a walking tour.