By Dr. Curtis Varnell

For much of Arkansas’s early history, roads were abysmal. Travelers’ found roads that consisted of no more than wagon tracks through the forests and marshes. Tree stumps, cut just below what was thought to be the height of wagon axles, dotted the roadways. During the rainy season, the roads became impassible quagmires of mud and swollen streams provided obstacles that the hardiest of travelers found impossible to traverse. The steamboat, an oft forgotten part of our past, became the most important means of transportation for the state.

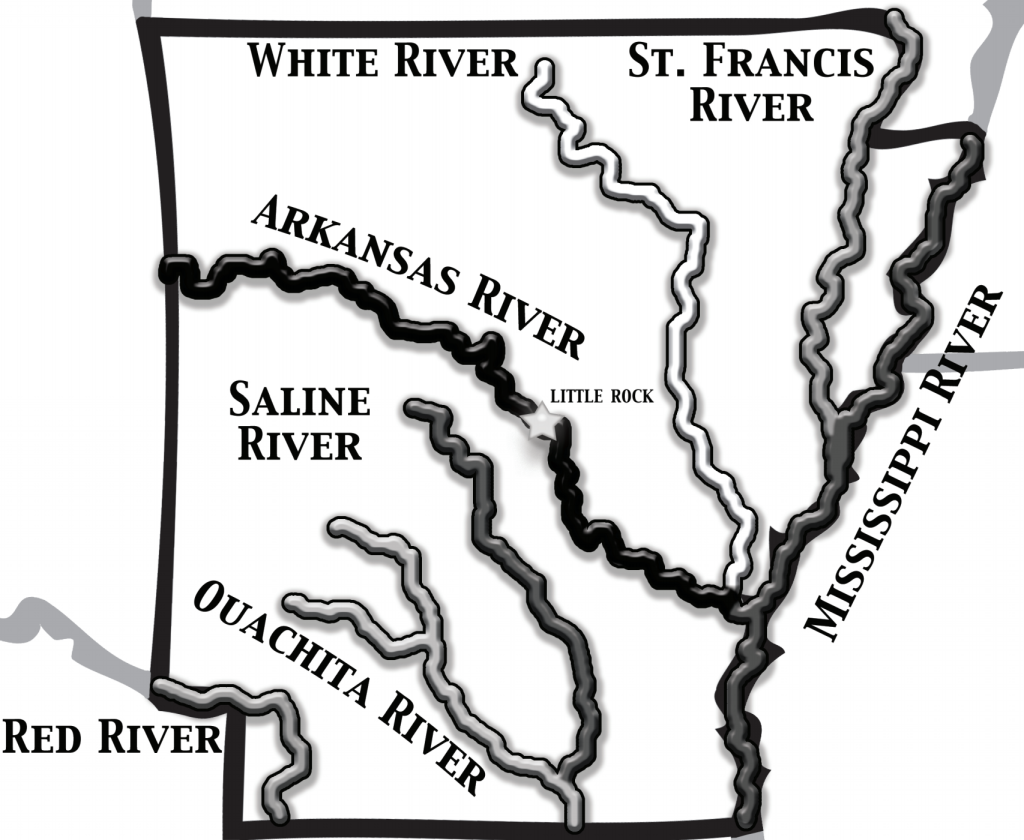

Everyone remembers studying the miraculous invention of the steamboat by Robert Fulton in 1807 but few realize how rapidly this mode of travel became of importance to the U.S. expansion to the west. Within years, steamboats plied the Ohio and Mississippi River, carrying every imaginable good to the frontier. Arkansas towns along the Mississippi were a part of that trade. In 1820, the Comet made stops at Arkansas Post on its way to New Orleans. Two years later, the Eagle steamed by Little Rock on its way up the Arkansas River to Dwight Mission near present day Russellville. Later that year, the Robert Thompson was able to steam all the way to the Arkansas border at Fort Smith.

The original steamboat, as developed by Fulton, required too much depth of water to navigate on most of the rivers in Arkansas. Henry Shreve, more famous for clearing the Red River of the its raft of fallen timber, engineered a boat with such shallow draft it was said to be able to traverse water less than a foot and a half deep. The typical Arkansas steamboat was long and narrow, not much different than a keel boat with an engine. The hull of the boat was virtually flat and contained little or no cargo. Decks or cabins were stacked above the hull with the first deck containing the engines and boilers. Looking little like the romantic boats depicted in history, cargo was stacked on the main deck. The passengers’ cabin and a kitchen was on deck two, and the pilot’s quarters sat above that. Many of the boats had hulls wrapped with iron bands which helped to hold the boat together when it encountered snags or rocks. The average life-span for an Arkansas river boat was five years.

Smaller versions of the steamboat steamed up the Ouachita, the Black, and even the Buffalo River but most could operate only a few months during the high-water stages. The Arkansas River could not be traversed above Dardanelle for a big portion of the year. Journals from the Trail of Tears years of the 1830’s describe passengers debarked from boats west of Conway and forced to walk for miles along the riverbank until sand-bars and rapids were traversed. Rivers constantly changed course, sand bars developed, and tree snags often blocked passage. In 1874, the Trader travelled far up the river to Batesville. Realizing the water was too shallow to proceed, the pilot turned his boat downstream and tied up to a tree for the night. The river dropped even more during the night and he found himself fifteen feet from the water line the next morning. His boat remained stranded for thirteen months before the river flow became great enough to travel again. Even more dangerous than the physical hazards were the steam explosions that could occur when the boilers became encrusted with mud and erupted, destroying the boat and many of its passengers. The Sultana explosion of 1865 is said to have killed more than 1,500 men returning from Civil War prison camps. The river boat captains that could avoid these hazards were revered. Mark Twain, a famous steamboat captain himself, stated “a pilot has to know the river with such absolute certainty that he could steer by reading the picture in his head rather than the one before his eyes.”

Steamboats opened up Arkansas to the world. The whistle of the steamboat as it approached shore was an anticipated event and everyone in the community would stand and await the boat’s arrival. The boats provided the means for farmers to deliver cotton, corn, wheat, and livestock to outside markets. Steamboats, running on regular schedules, delivered passengers, mail, and luxury goods such as piano’s, fancy dinnerware, and furniture to those wealthy enough to purchase the goods. For more than seventy-five years, the steamboat was the driving force behind the economic and cultural growth of the state. After the Civil War, railroads boomed and, just as quickly as they arrived, the steamboat disappeared. The paddles no longer turn, the whistles sound no more, and the days of the steamboats are part of a forgotten past.