By John Lovett

U of A System Division of Agriculture

While food safety is important year-round, the holidays bring the topic to the forefront as families gather to feast on a smorgasbord of hot and cold foods that can attract tiny, unwanted guests called pathogens.

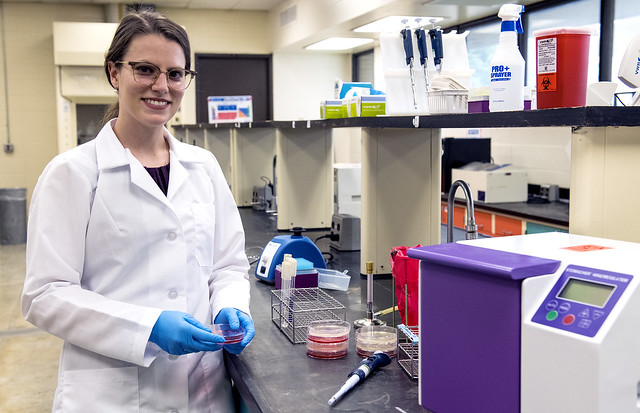

Jennifer Acuff, assistant professor of food microbiology and safety in the Department of Food Science at the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture, says all foods are subject to risk, but following food safety practices can help prevent sickness.

“We all eat food, and they’re all subject to some kind of contamination or risk every now and then,” she said. “My research gets to kind of pick apart those risks and try to figure out how we can protect consumers.”

Acuff conducts research for the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, the research arm of the Division of Agriculture. Her current research focus is related to food safety in low moisture foods, like powders, nuts, dried fruits and spices.

Temperature is key

Several factors contribute to a pathogen’s ability to grow to dangerous levels, but temperature is the easiest to control at home, Acuff said.

“Certain factors like temperature, the atmosphere, nutrients, and water … those all play a part in how bacteria grow. And one of the most important ones that consumers can control very well is temperature,” Acuff said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the top five germs that cause illnesses from food eaten in the United States are Norovirus, Salmonella, Clostridium perfringens, Campylobacter and Staphylococcus aureus, also known as staph.

Each pathogen has a different level of an “infectious dose,” or the number of bacterial cells required to get someone sick, Acuff added. So, someone can’t look at a food and know if the bacteria have reached an unsafe level, she said. That’s why she and other food safety experts generally recommend people not leave food sitting out at room temperature for more than about two hours.

“We have a lot of good data that shows above two hours is really pushing the limit on allowing dangerous bacteria to grow to dangerous levels,” Acuff said. “If you can just put up your leftovers you can stick to the normal family fights of politics and religion,” Acuff said. “The last thing you want to do is add on fighting over a toilet to that, or a trash can.”

If prepared foods like turkey and dressing, honey ham and deviled eggs are left at room temperature too long, they enter what is called the “danger zone” and give bad bacteria the perfect breeding ground to grow to harmful levels. That “danger zone” is between 40 and 140 degrees, Acuff said.

“A lot of the foodborne pathogens that we get sick from really enjoy our body temperature,” she said. “So, at room temperature, about 70 to 80 degrees, they grow very well.”

Besides leftovers, thawing frozen meats inside the refrigerator is also a best practice, she added, to allow for even thawing and limit bacterial growth.

The makings of a shelf stable food

When foods have characteristics that prevent bacterial growth at room temperature, they are considered shelf stable, Acuff said.

With baked goods, low “water activity” levels often contribute to products being shelf stable. Water activity refers to water that is “free” in the food and not bound by something else like sugar. While high-sugar foods like jam and fruit pies have a high moisture content, their water activity is low. Water molecules in those foods are bound to sugar, which means bacteria present can’t access the water to grow, she explained.

A pecan pie, for example, may seem like a pie with a lot of moisture and ripe for bacterial growth. But harmful bacteria will find it harder to access that water because it is bound to sugar on the molecular level, she explained. Pumpkin pie, on the other hand, does not have as much sugar binding up the water, so bacteria will find it a more conducive environment, she said.

“If it has whipped cream on it, I’d definitely get it into the fridge,” Acuff said.

Hand hygiene and cross-contamination

Other than temperature control, Acuff said to pay close attention to hand hygiene and avoid cross-contamination between produce, ready-to-eat foods, and raw meats.

“A lot of foodborne illness gets transmitted person to person, and food plays a part in that, but using proper hand hygiene can go a long way in protecting your family,” Acuff said.

Any kind of food that has been handled — for example, a turkey that has been cut up to eat — needs special attention, she said.

“You might have washed your hands, but your hands are not sterile, so they are not completely without bacteria,” Acuff said. “After about two hours or so, some of the bacteria that came from your hands might have grown to an amount that could really get someone sick.”

In the food preparation stage, Acuff said she keeps in mind the “order of operations” by cutting up produce and then raw meats for cooking to avoid potential cross-contamination. Or she may also just use a different cutting board and a different set of knives and tongs on the items.

“If you bring home raw chicken and you mishandle it with not washing your hands well enough or rubbing your hands on a towel without washing them and then essentially cross-contaminating something else … you could get yourself sick just from a salad because you handled chicken 30 minutes earlier and didn’t maybe do the best things in your own kitchen,” Acuff said.

To learn more about Division of Agriculture research, visit the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station website: https://aaes.uada.edu/. Follow us on Twitter at @ArkAgResearch and Instagram at @ArkAgResearch.

About the Division of Agriculture

The University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture’s mission is to strengthen agriculture, communities, and families by connecting trusted research to the adoption of best practices. Through the Agricultural Experiment Station and the Cooperative Extension Service, the Division of Agriculture conducts research and extension work within the nation’s historic land grant education system.

The Division of Agriculture is one of 20 entities within the University of Arkansas System. It has offices in all 75 counties in Arkansas and faculty on five system campuses.

The University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture offers all its Extension and Research programs and services without regard to race, color, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, national origin, religion, age, disability, marital or veteran status, genetic information, or any other legally protected status, and is an Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer.