A large and excited group exited the train as it came to a stop at the small town of Blue Mountain. Magazine Mountain, with its tree-clad slopes and steep cliffs, loomed in the distance. The passengers, many from the flat delta lands of the South, eagerly anticipated a week or more of vacation time in one of the several hotels located on the mountaintop. Hot summer weather, humid conditions, and mosquitos were great reasons to temporarily migrate to one of the mountain elevations found in western Arkansas. The elevations offered a temperature decrease of ten degrees or more from the surrounding areas; that coupled with nightly breezes attracted hundreds of visitors to the area.

The first order of business was transport to the mountain lodges. Most traveled up the mountain on small hacks and wagons pulled by horse and mule. On the west end, the road terminated at the base of the cliff. A small trail, wide enough only for the smallest of wagons, lead to the hotels located on the mountaintop. Passengers exited the wagon and, either carried their luggage or hired someone to carry their belongings to the hotel above. A road ran the length of the mountain above, allowing access to the golf course, croquet lawns, or (eventually) to the amphitheater. Other train passengers exited at Havana and traveled by hack over Barber Ridge and thus to the mountain. Either way, it was a rough and jarring journey with drivers clinging to wagon brakes to prevent runaways and frequent stops to allow rest for the animals.

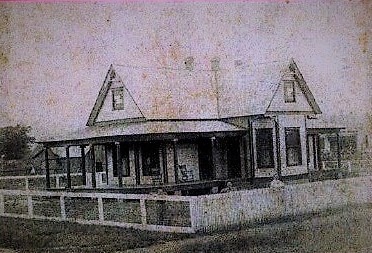

The first known hotel was the Skycrest Hotel on the west end of the mountain. It was built by the Choctaw, Oklahoma, and Gulf railroad and was well-regarded for its elegance and hospitality. A pavilion was built nearby. During the summer months, traveling bands and actors performed for the entertainment of guests.

Perhaps the most successful business was the Buckman Inn, built near McGuire Springs. It consisted of several cabins, a restaurant, an ice house, a croquet court, and a swimming pool. The swimming pool, constructed of native stone and sealed with tar, held the chilly waters collected from the spring. To access the swimming pool, one wandered down the mountainside for a few hundred yards, changed at the bathhouse, and then enjoyed lounging around the pool or swimming.

Another motel was operated by the Greenfields. Hattie Carraway, the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate, visited there and was impressed by the beauty of the location. F.C. Jones of Havana, the grandfather of Carol Burnett, often visited the area, bringing his family along.

Early advertisements offered rooms at two dollars a day or eight dollars and seventy-five cents per week. A menu from that period advertised a T-bone steak dinner with all the trimmings for one dollar and twenty-five cents. Most sandwiches were less than half that cost and coffee and other drinks were a dime. Even with those prices, which seem ridiculously low in our day and time, the mountain visits were only affordable for those from the upper-middle class. Relatives from that period of time recall living on the benches below the mountain top and seeing the lights and hearing the strands of music drifting in the night air and dream of what life would be like with a dollar in your pocket and a pair of shoes on your feet.

With the advent of automobiles, it became possible to take journeys to regions more distant. The lure of Disney land, beaches, and far-away sites drew people away from the mountain. By the 1930s, land on the mountain lost all value and the hotels closed. Today, only a few foundation stones and the remnants of the Buckman pool are all that remind us of those dog days of summers past.