By Dr. Curtis Varnell

A friend from Facebook recently posed a question concerning whether others had received their SNAP card for the summer. Living within a school district that is one hundred per-cent school free lunch, every student is provided a SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) card benefit which provides for lunch during the summer break. The card, essentially a credit card issued by the government, can be used to purchase food for low-income families or low-income regions.

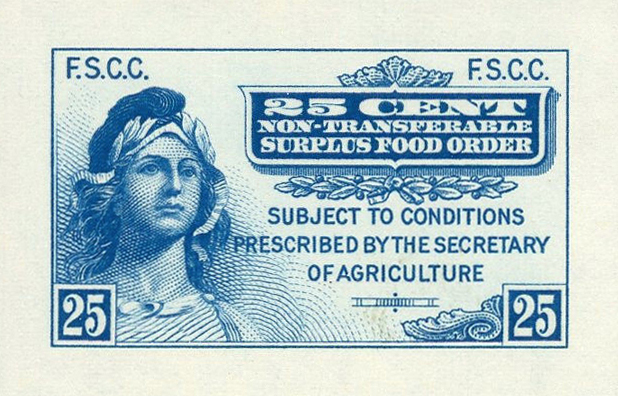

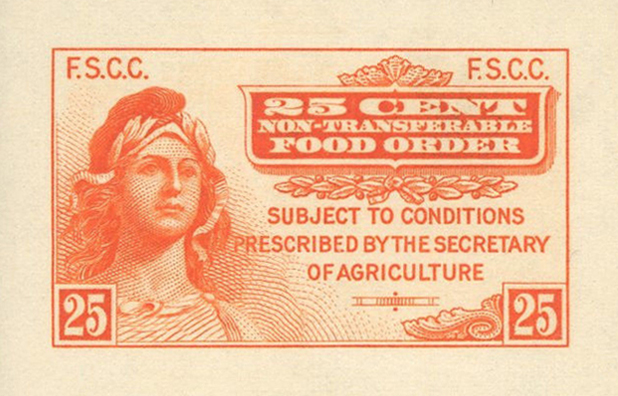

The entire program started back during the Great Depression. Under the Agriculture Adjustment Act, the federal government encouraged farmers to destroy surplus foods in order to drive up prices. Thousands of hogs were destroyed, gallons of milk poured out on the ground, and productive crops were simply plowed under; all in the hope that the economy would improve and farmers could make a decent wage. Many, horrified to watch the wanton destruction of produce while at the same time seeing millions suffering from malnutrition and even starvation, demanded that the government find a way to distribute the food to the needy. The government complied by setting up a program through the USDA to distribute the surplus through the non-profit Federal Surplus Commodities Corporation. By 1938, more than 54 million dollars in surplus food was being supplied to low-income families. As with today, this distribution lead to complaints of waste, the creation of informal markets, and concern about the “social” harm done to participants. One of the biggest concerns was voiced by merchants who felt that giving food away dramatically affected their sales. To address this, Secretary of Agriculture William Wallace set up the first food stamp program. The initial program allowed needy people to purchase orange stamps to be used to buy any food. For each dollar worth of orange stamps purchased, fifty cents worth of blue stamps was received free. The blue stamps could only be used to buy materials the USDA deemed surplus.

This program languished during the war years but was reinstated during the last year of the Eisenhower administration and grew during the Kennedy and Johnson years. No longer restricted to surplus items, the stamps could be used for most food products and had the support of retailers when it created financial gain for the producers and distributors of processed foods. The program, amended and changed many times over the years, has continued to expand to supply healthy and nutritious food to those in need. It also still faces some of the same criticism as was evident in the 1930’s. A big positive for Arkansas, in June of 2014, Mother Jones reported that 18% of all food benefits money was spent at Walmart.

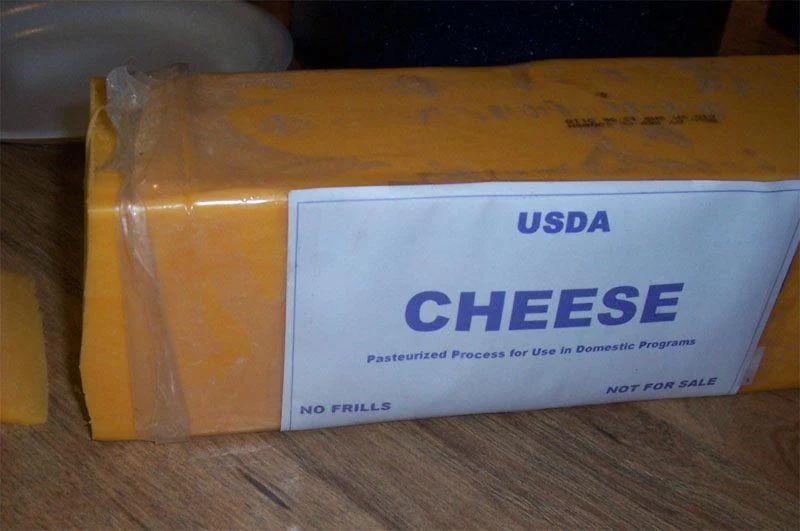

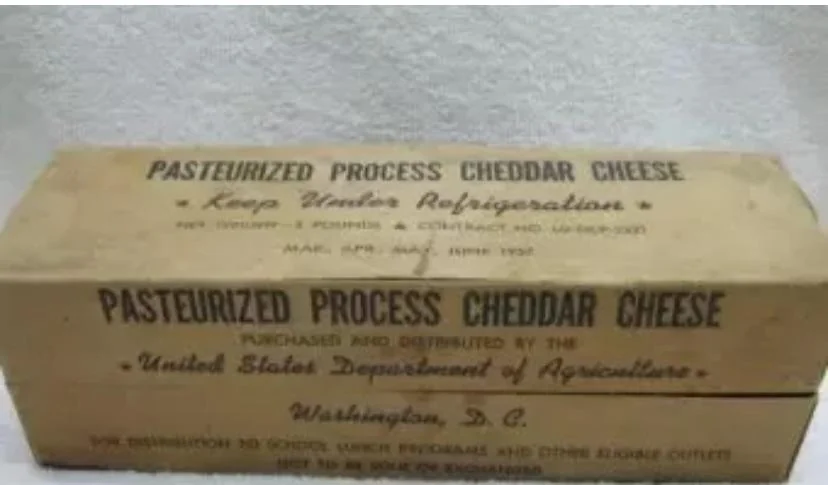

The food stamp alleviated much of the problem associated with food insecurity but did not alleviate the food surplus problem. To maintain markets, the USDA continued to supply excess “commodities” to the school lunch program and to those in need. Alarmed by the many military recruits that came in undernourished and under-weight from rural areas, especially in the South, the USDA set up a program to provide healthy food choices to low-income areas. As a child growing up in Arkansas, I observed lines forming hours before distribution of food to the general public. Many stood in line for hours, pulling a wagon or holding a sack to be filled with food. Termed commodities by locals, the products consisted of rice, beans, cornmeal, peanut butter, canned meats, butter, and powdered milk and eggs. Everyone’s favorite was the five-pound blocks of cheese; a mixture of cheddar, Colby, milk curds and other unknowns that resulted in a unique blend all its own.

Although few in the south wanted to be known as welfare recipients, few would turn down good, free food. My Oklahoma Indian grandmother always received extra, and others shared when they had more than they could use. The taste of the horrible, powdered eggs or milk were offset by the delicious cheese and peanut butter. We loved the rice but, in Arkansas, it is a breakfast cereal to be consumed with plentiful amounts of butter, sugar, and milk. The cooks at school turned the floor, sugar, and butter into wonderful concoctions of cake, cobbler, and cinnamon rolls rather than serving the pre-made peanut butter sandwiches provided today.

The program is still alive, but barely, occasionally supplying those over 60 or under income with surplus commodities. I often wonder if that “commodity” cheese is still available? I might go stand in a line myself!