By Dr. Curtis Varnell

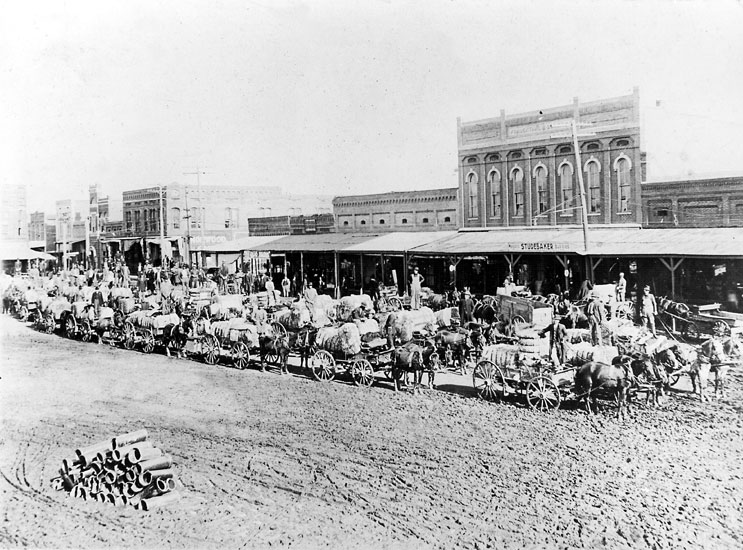

Driving from Pine Bluff to Eudora, one quickly can observe that fall has officially began. The sides of many of the highways look as if a snowstorm has arrived; cotton fibers blown from the trailers cover the roadside. Cotton pickers churn through nearby fields, quickly cleaning the stalks and storing the cotton in vast containers until it can be processed at the gins. Cotton production is still a big industry in the state with Arkansas currently ranking fourth in cotton and cottonseed production. In 2014, 820,000 bales of cotton were produced on 335,000 acres of plowed land. Still a big part of our economy, it ranks nowhere in comparison to its importance during the early history of our state.

Cotton has been a staple of Arkansas agriculture for more than two hundred years. First grown in 1803, by the 1830’s it was the most important crop the state produced. An ugly part of our early history, slavery was used to clear the fields and provided the necessary hard labor required to make a crop. After the Civil War, sharecroppers received from 25-50% of a crop for producing cotton on 40-acre plots owned by large landowners. Small shacks and cotton towns dotted the landscape; inhabited by poor whites and former slaves who struggled to make ends meet.

Beginning with my grandparents, my family were involved in the cotton industry. Many of the mountain people raised upland cotton on small fields and hollows in the Ouachita Mountains. Production was generally poor and not enough to support the large families of the time period. As a result, many became migrant farmers who travelled to the delta for work. My grandfather and his friends would often plant their crop and leave one family member to work the fields they owned. The remainder of the family traveled to the delta to work the cotton fields. Many of the migrants did not have available transportation. As a result, the property owner would send out a notice telling people when he would be in the area. A large flat-bed truck was then sent to pick up workers. One spring, my grandfather had a cow that had just calved. Not wanting to leave the cow, he persuaded his employer to load the cow onto the back of the truck with the family for the drive to the fields in Lonoke county. That was surely a sight as they traveled down the highway and through Little Rock with a half-dozen teen boys, my grandparents, and a jersey cow.

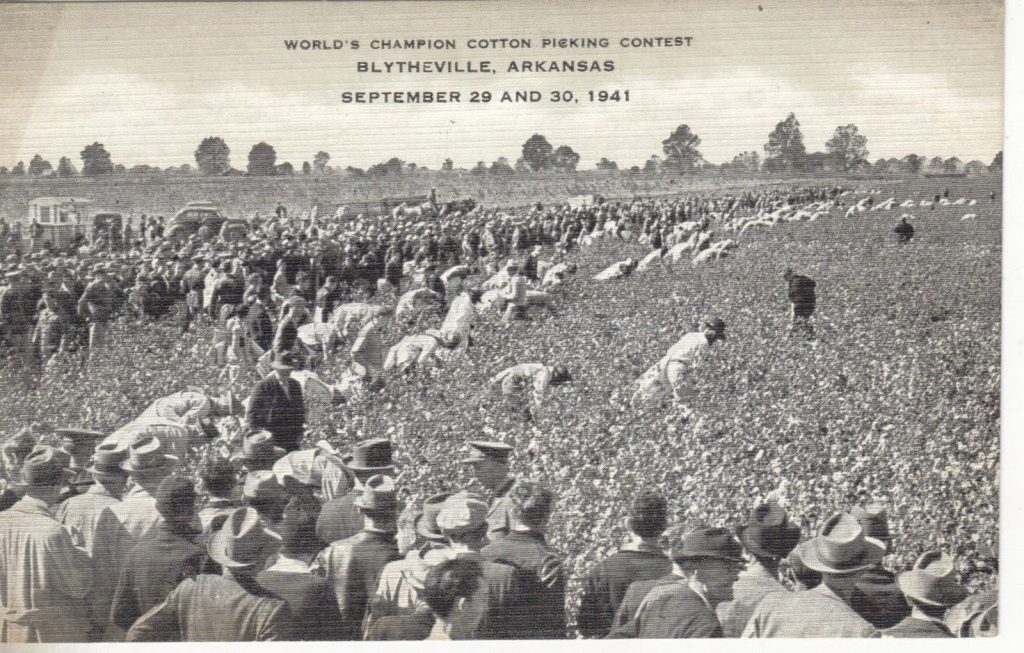

My grandmother was a champion cotton picker. Pulling a loose sack hung about her shoulders and picking rapidly with both hands, she could out-pick any two of us. Cotton picking contest were held in many towns to determine who could pick the most cotton in a ten-hour day. I am not sure grandma every tried that but my money would have been on her.

Picking cotton is only a small part of the job. In the spring the cotton had to be planted in long straight rows, sometimes a mile in length. My father was good at driving a tractor and laying off straight rows so that was his spring job. On Saturdays, he was allowed to take the tractor, hook on a trailer, and the workers in the cotton camp would climb aboard for a ride into England, Arkansas for a day of relaxation, shopping, or watching a movie.

After the cotton came up, it had to be thinned and then weeded. By 1960, the going rates for chopping the cotton was $1 dollar an hour for a ten-hour day. Fifty dollars a week was considered a good salary for the time period. In the late 1940’s, my granddad made enough extra over necessities that he had enough extra money to buy a length of sheet iron each week. Saving them up over the summer, he was able to buy enough to take home in the fall and cover the leaking wooden shakes that covered their home.

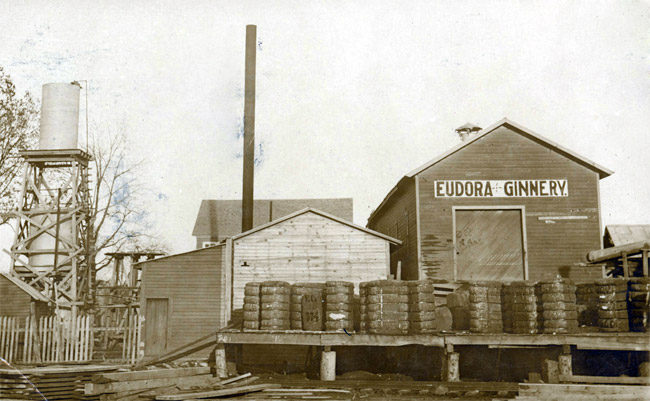

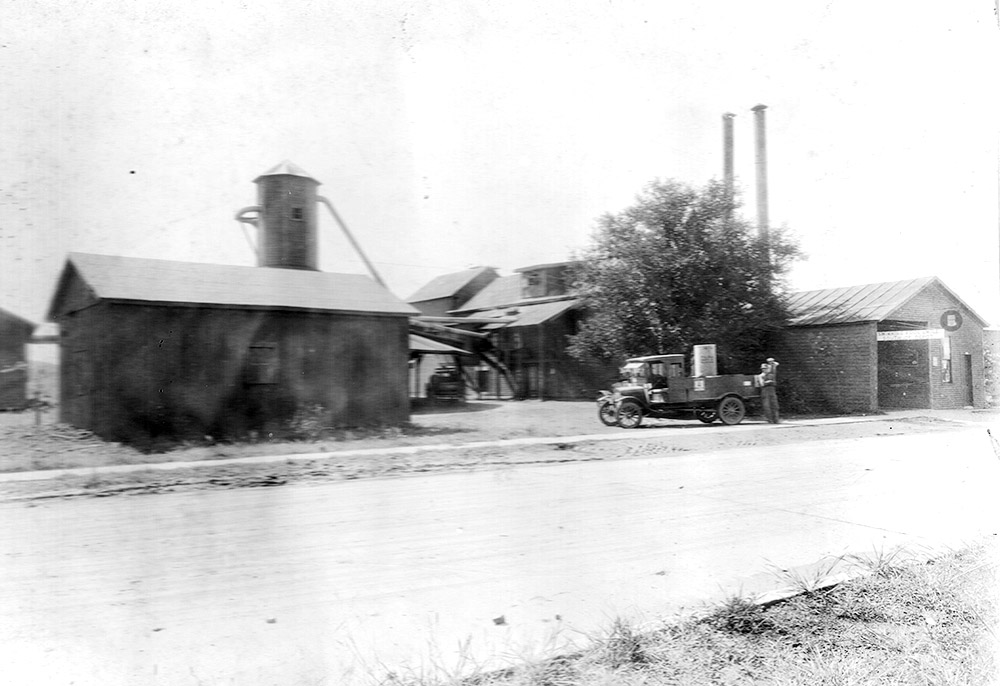

In the fall, cotton gins processed the cotton. A large vacuum sucked the cotton from the trailer, carded the cotton from the seed, and then pressed it into large bales. My father, always a hard worker and mechanical, could operate nearly any machine in the gin but they generally had him placing the metal belts around the huge bales of cotton and rolling them off the press, ready for distributing to the cotton merchants in Memphis.

By the 1950’s, cotton pickers and machinery eliminated the need for large number of laborers. My parents started migrating North to Illinois and working in the canneries during the summer. Towns in the Delta began to decline in size and importance and some of the cotton plantations switched to soy bean and rice but cotton still remains a part of our legacy and an important contributor to our economy.