By Dr. Curtis Varnell

Travelling upstream, the keelboat struggled against the current. Moving to the landing on the north bank, a layer of dark black rock caught the eye of explorer Thomas Nuttal who noted it in his journal. The location was Spadra Landing, Johnson County, Arkansas and the year 1819. The black layer of rock was identified as a bituminous coal layer and became one of the most valuable materials mined in the state.

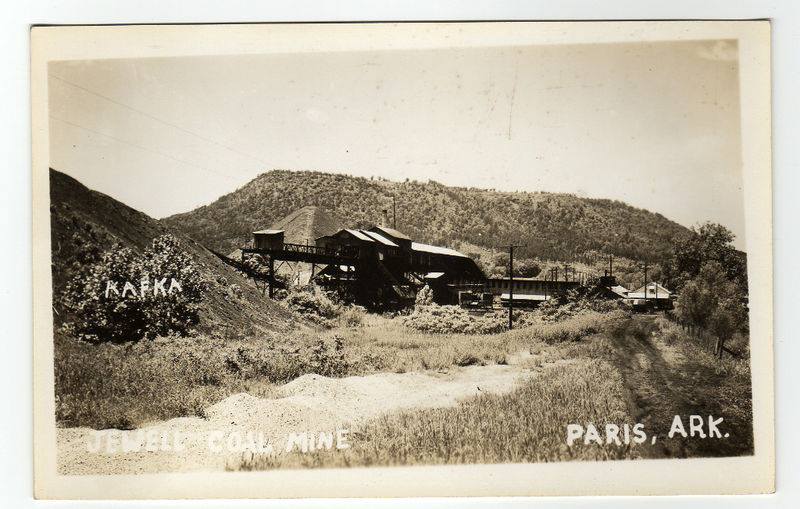

Eventually coal fields were found to exist in a 33- mile-wide, 60-mile-long area running from Russellville in the east to the western border of the state. As pioneers moved into the area, they began to extract small amounts of the coal to be used as heating fuel and for blacksmith shops. Some more enterprising individuals began to extract larger quantities to ship to New Orleans and larger towns, selling the black rock on the open market. Trains, fueled by coal, vastly increased the demand for coal and, by1880, Arkansas coal was fueling the development of the west. Greenwood to Hartford in Sebastian County was the center of the coal trade but huge mines existed in Johnson, Franklin, Pope, and Logan counties as well. In 1907, coal mined in Arkansas reached a peak of 2.6 million tons. Over 106 million tons of coal were produced from 1880 to 2006. Mineral rights to one mine, Greenwood #2 in Sebastian county, sold for over two million dollars while, at Paris, 13,000 railroad cars of coal were shipped out in an eight-month period of time.

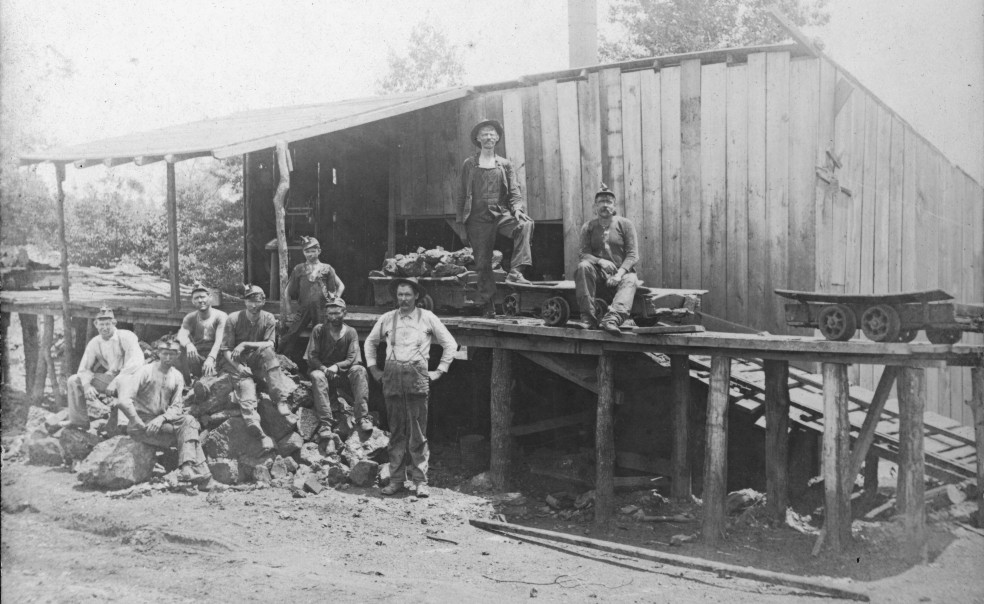

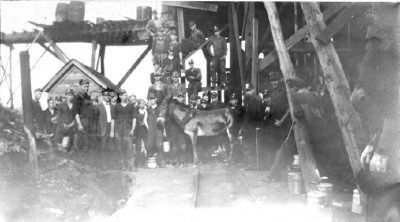

Fortunes were made but not by the hard-working coal-miners who extracted the coal. Working for an average of 75 cents an hour, they risked life and limb and they crawled into mines sloping downward from the surface. Using a pick and shovel, they removed the coal from between sandstone rock layers that shifted and settled from the tremendous weight above. As more coal was demanded, the miners crawled on hands and knees into darkness lighted only by carbide lamps, set dynamite into the coal layers, and waited in the darkness as the tremendous charges shook the earth loosening the valuable coal for extraction. Newspapers were filled with stories of the resulting toll on life and limb. Working on my dissertation, I interviewed several older miners. Alan Heard of Greenwood described the worst day of life, “My dad and I were in the Excelsior mine near Hackett. Hearing a loud noise, my dad screamed for us to lay down on the floor. Instantly, blue flame flew up the tunnel, scorching our clothing and burning exposed flesh.” Seven men were killed in the explosion, their bodies carried out by fellow miners who worked hours to remove them from the entrapment. Three of the men killed were brothers. Most mine accidents were smaller in scale, involving the death of only one or two individuals. Falling down a shaft, electrocution, being kicked by a mule, or hit by falling rock were small in scope but contributed to a cumulative large sum of people, all tragedies on a smaller scale. More insidious was the damage done to health as the workers breathed the dust resulting from mining. As they aged, black lung afflicted the respiratory systems, resulting in coughing and black spittle from bleeding in the lungs. Worn our backs and limbs resulted in painful arthritis, robbing years from the miner’s lives. As H.B. Stewart, a one-time miner and long-time Greenwood coach told me, “Miners worked hard, lived hard, and died young.”

A hard life but one that that made a decent living for the family, many of the men told me that they wouldn’t change the life they lived for any other. As one of the miners explained to me, “millions of dollars of coal came out of those mines. The coal fueled the growth of America and, during WWII we would not have won without coal as a fuel source. So much good came out of the rock but, at the end of the day, the most valuable thing to come out of that mine was the miner.”