By Dr. Curtis Varnell

The Indian Removal Act was passed in early 1830, resulting in one of the most dismal periods of Arkansas history. More than 60,000 members of the five civilized tribes were forced from their ancestral homelands in the east and resettled in Indian Territory. Unwilling for the most part, these people had little choice but to uproot from lands they had owned since antiquity and herded west to “relocate” in what is now Oklahoma. In most cases, military accompanied by hired contractors, were given the task of guiding the natives to their new homes. These contractors, paid by the head to deliver the tribes to their new home, sought the easiest, fastest, and cheapest routes of delivery. The result was a multitude of pathways and means of delivery, all having a common denominator of hardship, disease, and often death.

Most of the pathways westward included portions of the trip traveling in caravans with wagonloads of possessions, often walking barefoot beside the wagons along primitive roads and trails cutting through forest and swampland. The decade of the 1830’s saw miserable summer and extremely cold winters, factors which were often ignored by contractors and military who were consumed with getting the goods delivered as rapidly as possible. Untold numbers of tribal members died, the results of dysentery, measles, and other communicable disease.

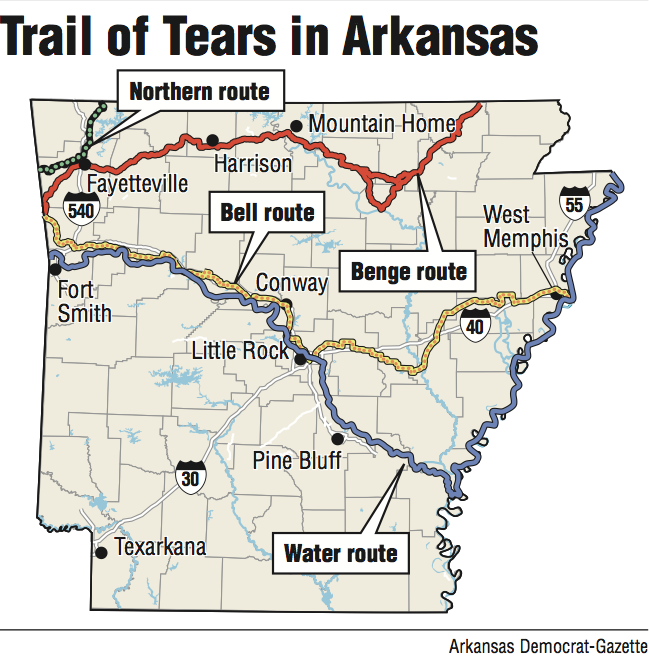

Many of the Cherokee came through the Northern route which passed through Missouri and then down the Fayetteville road to Fort Smith while the other tribes more often traveled up the Arkansas River as far as possible and then up the Military road running from Little Rock to Fort Gibson as the water became to shallow to traverse. The journal of Lt. Edward Deas, shared to me by my friend Dusty Helbling, describes in detail many of the hardships.

Deas, and his contingent of Cherokee, had arrived in Little Rock on April 11th of 1838 and were some of the last group of Cherokees to make the journey. Finding the steamboat that had delivered them thus far too large to travel westward, Deas arranged for the smaller boat, the Little Rock and two accompanying keel boats, to deliver the group to Oklahoma for $5 a head. The journal describes the difficulty experienced by the group as they travelled. A day out of Little Rock, one of the keel boats sprang a leak when it encountered a hidden snag. Landing on shore for repair, they found that that area residents were plagued by small-pox. Leaving one of the keelboats and most of the supplies, they proceeded with all dispatch on up the river. The boats constantly encountered sandbars and shoals. When this occurred, the travelers were put ashore and walked miles through the underbrush until bypassing the obstacles.

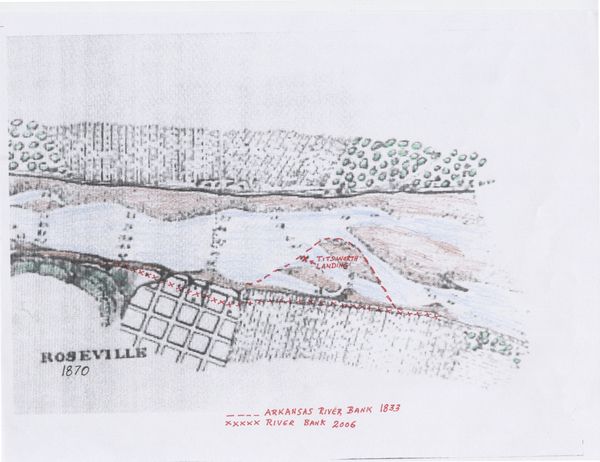

The group encountered a storm on April 17th and, facing a strong wind, could not make headway and the tents, set up on shore, offered little or no protection. On the 21st of April, the group reached Titsworth Landing, a plantation near the current small town of Roseville, AR. With water too shallow to proceed further, the group were offloaded and wagons were rented to transport the group from there into Fort Smith.

The group traveled south by wagon, joining the old Military road near the current town of Caulksville and then west. Spending the night on Vache Grasse creek, Deas casually mentions that two of the small children had passed away in the night and were buried along the stream near what is now Central. This was not uncommon. The 1834 group of 500 Cherokee camped near Cadron (Conway) reported losing 81 members of their party when a cholera epidemic swept through their camp. Way too many other groups reported similar losses.

Nearing the end of April, the party eventually arrived in Fort Smith and were dispersed over the river and into Indian territory, completing the journey on the trek known as nunahi-duna-dlo-hilu-i— “the trail where they cried.”