By Dr. Curtis Varnell

Until the middle of the last century, trains were the primary means of travel for most Americans. Virtually every town had a train depot and the whistle and roar of trains passing through a town was a common occurrence.

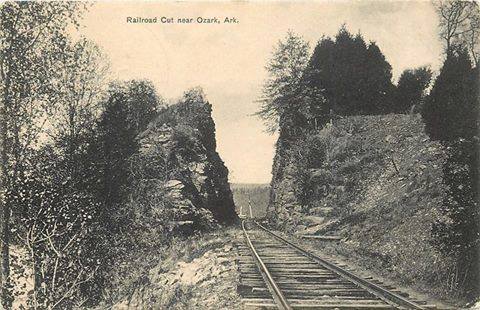

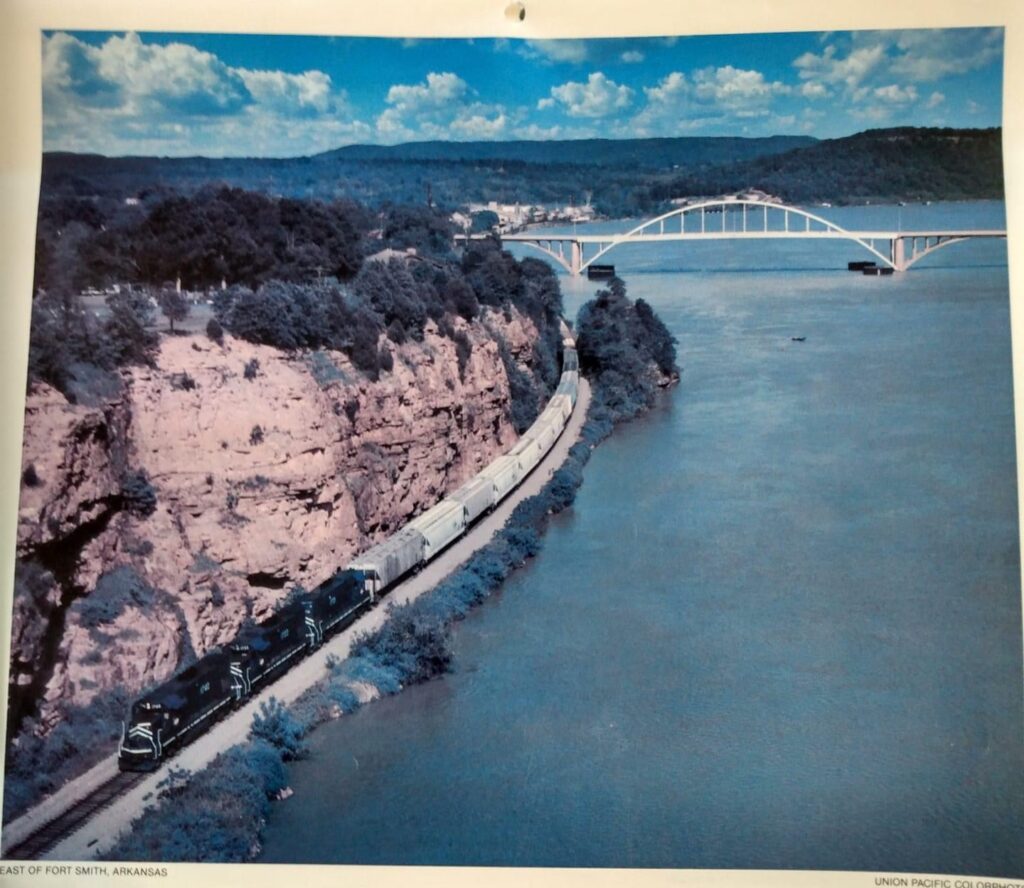

When the Civil war ended, Arkansas had only thirty-eight miles of track in the entire state. That quickly changed and rapid expansion of railway systems soon created railroad lines across the state. By 1874, Fort Smith became the center for the north-south track running from Cairo, Illinois into Arkansas and eventually, fueled by local coal, through Hackett, Hartford, Mansfield and further South. The east-west line ran from Memphis, through Little Rock, Clarksville, Ozark and into Fort Smith. The competing lines were eventually bought up by Jay Gould, one of the big time financial giants of the age of expansion. Gould once visited Fort Smith is his state-of -the art coach and hundreds showed up at the station to view the financial giant only to have him remain in his coach, too important and elite to concern himself with the locals.

By 1890’s, various railways began to expand into smaller communities. Fort Smith, Charleston, and Paris contributed money and land to the rail system to begin expansion down what is now highway 22 and the first train arrived in Paris in 1898. A year later, the Rock Island connected Fort Smith to Mansfield, Booneville, and then into Ola. The initial impetus for expansion was the transport of farm products, especially cotton, to the international market. When high grade coal was found in Charleston, Paris, and later Scranton, trunk lines were built into those towns connecting the entire region with Dardanelle.

The rail system opened up the world to the scattered and isolated regions. People from the delta began taking excursions to the mountaintops of Nebo, Magazine, and Petit Jean in order to escape from the summer heat and humidity. Hotels, complete with swimming pools, golf courses, and even running water were constructed to relieve the tourists of their excess greenbacks. One today can little imagine the willingness of a person to exit a train at Dardanelle, Havana, or Blue Mountain and take a horse-driven hack miles up the side of a mountain to spend a few days in a rustic retreat. On Magazine Mountain, the terrain was so rough that passengers had to walk carrying their luggage up the last few hundred yards.

Locals took shorter tours, traveling to Confederate park in Charleston to picnic or to Mansfield to play the locals a baseball game. Sunday travel tours were common with people dressing in their Sunday best for a coach ride through the country side. At Blue Mountain, one could exit the train, travel up the mountainside a few miles to twin falls and enjoy man-made swimming pools complete with changing areas, a dance floor, and probably some illegal moonshine during prohibition days.

Bonneville was a divisional center for the Rock Island and a layover point for rail employees. Its extensive depot became the Grier house restaurant and was a favorite dining and lodging place for travelers throughout the region.

With the ending of WW11, travel changed to the automobile. Coal fields closed down, agriculture moved to California and points west. Slowly, the rail systems to small towns stopped, the depots crumbled or burned, and a way-of-life ended. Remnants of the lines remain, a bridge here and there, the old upraised rail road path, and in a few places, rusted train tracks that now lead nowhere.