By Dr. Curtis Varnell

The Pig trail on highway 23 feels deserted on a cloudy September morning. From the top of the mountain, the sun could be seen rising above the peak to the east. In between, a gulf of low-lying clouds gave the appearance of being stranded on a mid-ocean island. A sea of shimmering white caps separated the two mountains. As the sun rises, the clouds began to flee, leaving tendrils of steam rising through the darkness of the forested slopes. Car motors strain as the tires grip the pavement, struggling to overcome the steep slope and hairpin corners. Surrounded by the silence of the Ozark National Forest and miles and miles of unbroken wilderness, it’s hard to imagine that this pristine area was the scene of an intense forestry industry and was bisected by railroads that carried the forestry products to market.

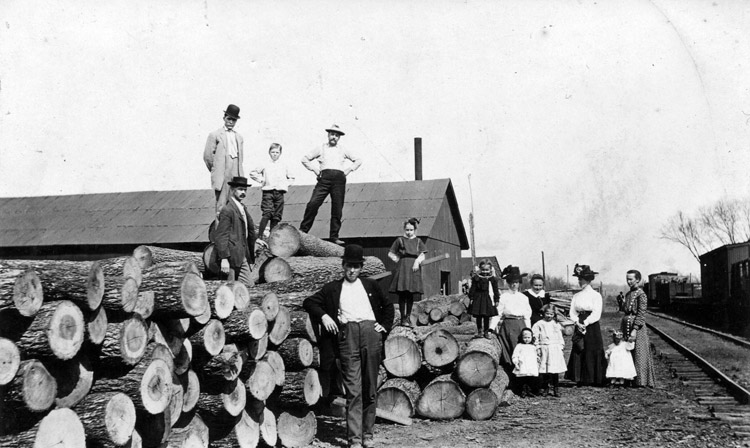

A common statement is that money can make water run up-hill; it can definitely move mountains and create access to markets when enough money is involved. The Ozarks and Ouachita mountains were covered with large trees which, when harvested, could be sawed into lumber, railroad ties, barrel staves, and other wood products. With the roaring economy of the early 1900’s, there was money to be made if the product could be made assessable to the world market. Large rail systems existed north and south connecting Springfield, Fayetteville, and Fort Smith to the outside world. Smaller branch lines began feeding into the countryside, providing transportation to markets and the lumber industry was booming. By 1913, rail had been laid along the White River through the small towns of Combs, St. Paul, and on to Pettigrew. Sawmills, powered by steam engines, dotted the landscape, providing the timber needed for American industrialization.

Large unharvested supplies of raw lumber could be found in Northern Franklin county but it was difficult and expensive to get to market using wagon and mules. Wanting to tap the vast supply, the J.H. Phipps lumber company of Fayetteville, Arkansas determined to build a rail system over the mountains from Combs to Cass. What became knowns as the Black Mountain and Eastern was one of the most unique railroads ever built. The 17 difficult miles between the two small towns required a train to go up nine steep miles to the 1,900 ft. peak of Summit Mountain above Cass and then descending eight miles downward to Combs. The line required four wooden bridges, two of which were more than 100 feet high and one that was 385 feet long. In four places, the curves were so sharp that extra spurs were added so the train could run out onto the spur, back up, and then complete the turn.

Construction was slow, reaching what was known as high Cass in 1916. The slope from what was known as high Cass to the town of Cass was so steep, the railroad eventually built a switchback that would allow trucks equipped with two motors and railroad wheels to move goods from Cass to the top of Cass Mountain.

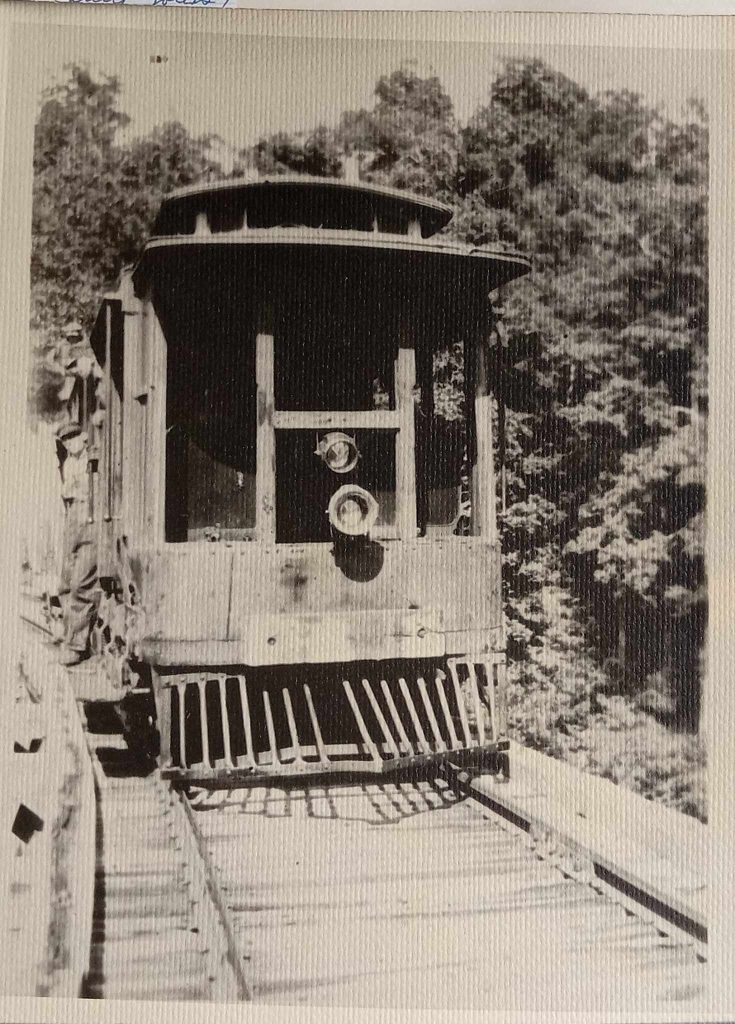

The railroad consisted of five cars, two of which were boxcars, and then flatbed cars to haul timber. During the final five years of operation, the railroad purchased an old street car powered by gas motor and it carried passengers back and forth from the various communities. Somewhat sporadic, the street car would sometimes hold up rail traffic for hours waiting on a single customer.

Jay Fulbright acquired the controlling interest in the railroad in 1918 and, upon his death in 1923, his son J. W. Fulbright became the youngest railroad president in the U.S.

As the timber industry slowed, the railroad began to lose money and was closed in 1928. All that remains today is a few earth embankments, the foundations for the trestles, and a few rock escarpments where rock was blasted away for the roadbed. The old passenger car, Car No. 10 is located at the Ft. Smith Trolley Museum awaiting restoration.

The narrow highway is covered by overhanging branches from trees along the roadway. Rocks tether on steep slopes, looking capable of releasing tenuous hold in the shallow soil and tumbling down the mountainside, and modern cars struggle up and down the steep grades. One of the most beautiful and scenic highways in America, it is hard to conceive that man could ever construct a machine that could conquer these mountains but the Combs to Cass railroad done just that.