By Dr. Curtis Varnell

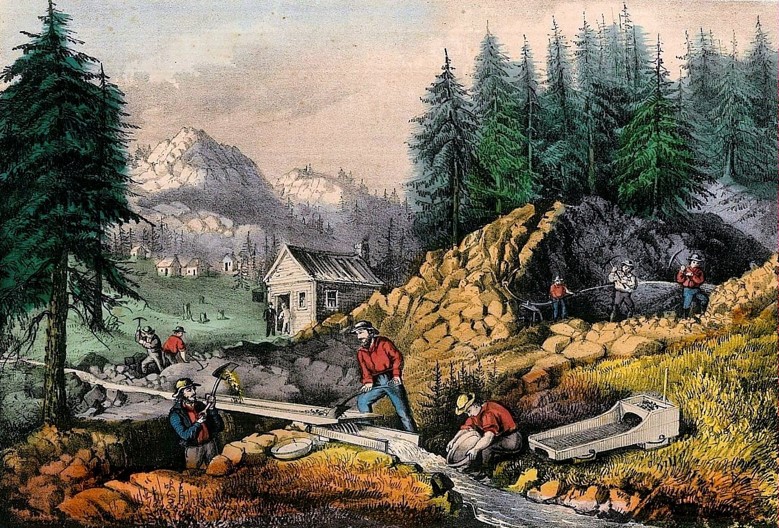

Something about the heavy, shiny metal has always attracted mankind. From our earliest history, the lure and acquisition of the metal has been a prime motivator worldwide. Rings made of gold mark the everlasting circle of love and life, crowns formed from it denote authority, and the person who can acquire sums of it is a person of wealth. The love relationship that man has with the substance has been deemed the root of all evil and the lust to acquire it has been deemed the Gold Fever. Man has forever sought for natures hidden locations of this treasure. In the year of 1848, the motherlode of all locations was discovered near Sutter’s Mill, California. News of the discovery spread eastward like wildfire. In the 1848 State of the Union message, President James Polk confirmed the rumors by announcing that there was indeed gold and California and plenty of it for the taking. The announcement touched off the event known in history as the California gold rush and the people involved as the 49ers.

Arkansas, and most of the U.S., was mired in an economic depression marked by high inflation, lack of funding, and huge personal debts. California looked like a godsend with wealth just waiting to be picked from the hillsides and streams of the new western territories.

Senator Borland of Arkansas immediately realized the possibilities of developing Arkansas as the jumping off location for trails westward. Most trails westward began further north, passing through Independence, Missouri and following the Oregon trail. Borland felt a more natural trail would begin in Arkansas and follow a southern route through Santa Fe and then on to California. Using his political clout, he was able to obtain a military guard that would accompany the first wagons as they crossed dangerous Indian territory into New Mexico.

The expeditions were set to gather at jumping off places. At these locations, groups would organize into trains with guides that would lead the journeys west. In Arkansas, three jumping off centers developed; Fort Smith, Van Buren, and Fayetteville. The Fort Smith and Van Buren group planned to follow the southern route and the Fayetteville group planned to use the Oregon trail. All three routes were essentially undeveloped paths through trackless wilderness and exacted unimagined hardships on those brave enough to attempt the journey. It is estimated that more than 3,000 immigrants and 900 wagons left from the Arkansas sites. Most were men but, a few women accompanied the trains. It is worthy of note that several journals mentioned that women did as well, and in many cases, better at facing the hardships than the men.

Journals record the travails of travel. The large “Clarksville’ group of more than one hundred men, were some of the first to leave Fort Smith. Leaving as soon as the grass was high in early April, they quickly discovered that the spring rains had turned the roads to quagmires and the rivers into roaring angry torrents of water. Organization soon deteriorated and trains broke into smaller and smaller groups. Some men, exasperated by slow travel and broken-down wagons, loaded their goods on mule packs and travelled on alone. Wagons, furniture, and goods littered the roadsides, left by owners realizing that they could live without the items easier than they could pack them to California. At Santa Fe, the troops left the expedition and turned back home. Travelers faced a choice of three routes, none of the them easy.

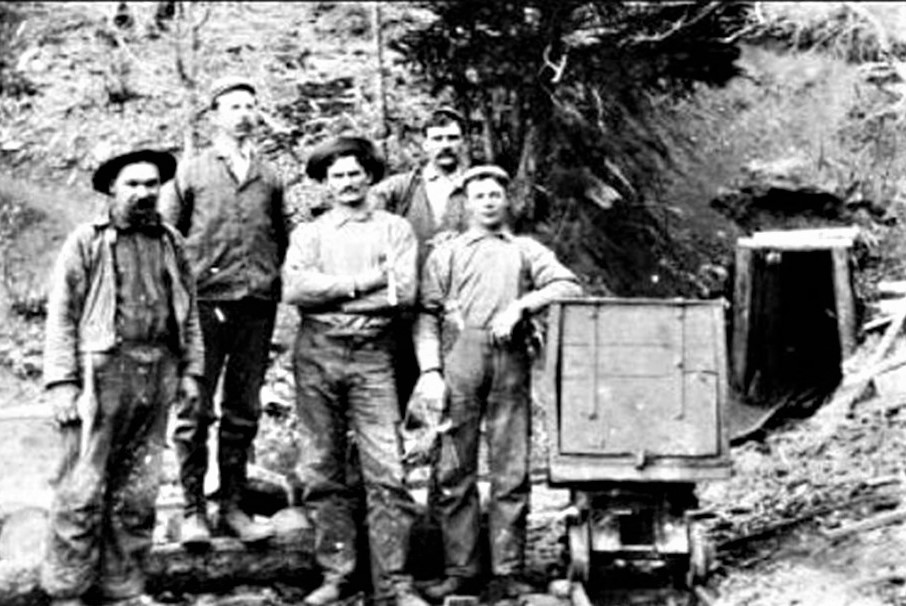

The Clarksville group eventually arrived in California during December, the middle of the rainy season. Some went immediately to the gold fields, others found temporary work in the businesses providing goods to the miners. Wages were good but expenses were high. They might extract $10 a day from a good site but room and board ate up most of the funds. It was said that from every hundred that arrived in California, 50% would have been better off to have remained home while 4% did well and only 1% became wealthy. John McVicar of the Little Rock Company hit it big when his mine struck a vein of gold, enough that partnership shares in the company sold for 1$18,000. James Jarnagin from Johnson county found one nugget that weighed in at 23 pounds, 11 ounces. James Garner, a man who eventually became a legislator and the first sheriff of Logan County, found enough dust to fill a teapot. He travelled home around the horn of South America and back to New Orleans. At home, he purchased property and established a large farm and mill. During the Civil War, the gold from California sustained his family. His family still own the teapot and other artifacts from his travels.

More than a million people poured into California territory during the gold rush, enough to establish it as a state. Taxes from the gold funded the Union during the Civil War and the routes established westward still exist, all the result of the California “Gold Fever.”